Things are changing in comics—and one sign of that change is Batgirl.

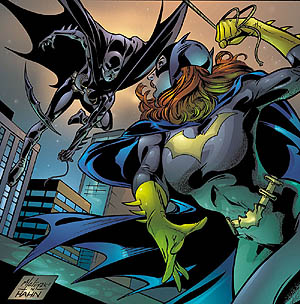

Superhero comics are for guys. Specifically, the audience for superhero comics has, consisted of men in their 20s-40s. That's reflected in the heroes (mostly men) and in the portrayal of women (mostly scantily clad).

Or at least, that's been the case for quite some time. But movies have helped broaden the audience for superheroes, and digital distribution has created the possibility to reach readers who don't frequent comics shops. Things are changing—and one sign of that change is Batgirl.

Batgirl has been around for decades, of course. But her most iconic moment of the modern era was probably in 1988's The Killing Joke, by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland. That was smack dab in the middle of superhero comics by guys for guys, and, consequently, Batgirl's role in the comic is to serve as a plot point for male psychodrama. She doesn't even get to put on her costume. Instead, in her secret identity of Barbara Gordon, she is shot through the stomach by the Joker, who then strips her naked and takes photos of her (he may or may not sexually molest her as well). This is all part of a plot that has nothing to do with Barbara herself; the Joker is trying to traumatize her dad, Commissioner Gordon.

Writer Alan Moore, who later regretted the story, said that when he proposed shooting and permanently wounding one of DC's highest profile female characters, his editor, Len Wein, responded by saying, "Yeah, okay, cripple the bitch." DC saw women heroes as fodder for abuse and humiliation—by supervillains and editors alike. In a fight between the Joker and Batgirl, guy readers, guy writers, and guy editors were assumed to identify with the Joker.

After this misogynist violation, though, Barbara Gordon had an unexpected feminist second life. Kim Yale and John Ostrander took the character, now wheelchair-bound, and turned her into Oracle, the computer genius and mastermind who became the center of the all-female Birds of Prey, most famously written by Gail Simone (who had criticized The Killing Joke.)

Simone, and Birds of Prey, were a bit ahead of their time in their focus on female heroism at the big two superhero publishers. But more and more these days, Marvel and DC have been moving to try to appeal to women readers. The new Batgirl comic, featuring a (once-again walking) Barbara Gordon as Batgirl, is one example of the new trend. The new Batgirl design is cute rather than va-va-voom—visually it references manga and indie comics, both genres that have historically had a higher percentage of female readers.

This change in focus has caused a certain amount of static among older comics creators and readers. Longtime artist Erik Larsen recently moaned and groaned on Twitter that he was "tired of the big two placating a vocal minority at the expense of the rest of the paying audience by making more practical women outfits." Larsen felt Batgirl should still be pandering to him because most of the comics audience is men. And he's right that most of the superhero comics audience is still men . . . but books with female heroes have generally sold badly to men. The audience for the new Batgirl comic is clearly thought to be (and I would strongly suspect actually is) mostly, or at least substantially, composed of women.

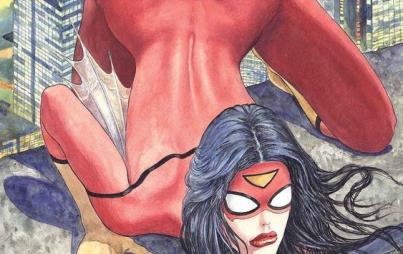

The transition from one audience to another also explains the controversy around this Batgirl cover. The image by Rafael Albuquerque was a variant cover intended to be part of a line-wide celebration of the Joker. As you can see, it references The Killing Joke by showing the Joker terrorizing a clearly traumatized Batgirl; he's painted a smile on her face apparently in blood, emphasizing her helplessness and humiliation. The image is about how cool the Joker is; it's for his fans, not hers. She's there to testify to his awesome creepiness, not to be the hero.

a line-wide celebration of the Joker. As you can see, it references The Killing Joke by showing the Joker terrorizing a clearly traumatized Batgirl; he's painted a smile on her face apparently in blood, emphasizing her helplessness and humiliation. The image is about how cool the Joker is; it's for his fans, not hers. She's there to testify to his awesome creepiness, not to be the hero.

But, of course, fans of Batgirl are fans of Batgirl. They buy her comic to see her being heroic, not to see her being a slasher movie victim. As a result, the cover sparked a major outcry. Realizing they'd made a misstep and alienated their target audience, DC and Albuquerque decided to abandon the variant. Albuquerque issued a statement in which he said, "For me, it was just a creepy cover that brought up something from the character's past that I was able to interpret artistically. But it has become clear, that for others, it touched a very important nerve." Or, in other words, he thought he was creating a cover for certain fans, but it turned out the audience was someone else. Corporate work-for-hire comics are in the business of catering to their readers. Thus, the cover was withdrawn.

The controversy has been picked up by elements of Gamergate (a description of which is here, if you're fortunate enough not to know about it already.) Christina Hoff Sommers, a Gamergate ally (who has little interest in comics, as far as I'm aware) tweeted at me that the Batgirl protests were "activism by Puritanical scolds." She and others suggested this was a threat to free speech.

There have in fact been threats around this matter; people who opposed the cover apparently received death threats. It's possible that the spectacle of people being harassed because they opposed the cover may have been part of what led DC company to drop it (to their credit). In any case, it's worth remembering that what we've got here is a work-for-hire cover featuring corporate characters, and intended (being a variant) essentially as a marketing ploy. This is not some sort of avant-garde personal creation. The variant cover was meant to sell comics. Albuquerque tried to sell comics by appealing to the fandom that would, once, have been Batgirl's audience—guys for whom she was most appealing as a violated chit in someone else's psychodrama. But Batgirl's fans, now, are there for Batgirl, not for anyone else.

Personally, I think it's a good thing that superhero comics are gaining a wider audience, and that DC and Marvel are growing more able to view women as creators, readers, and heroes, rather than just as sexualized cannon fodder. If you want comics where women are just sexualized cannon fodder, you can always go reread The Killing Joke (even though Alan Moore would rather you didn't) or any number of other superhero comics, past and present. Appealing to different fandoms isn't censorship, though. It broadens the range of possible expression; it doesn't narrow it.

An earlier version of this story misidentified the creator of Oracle.